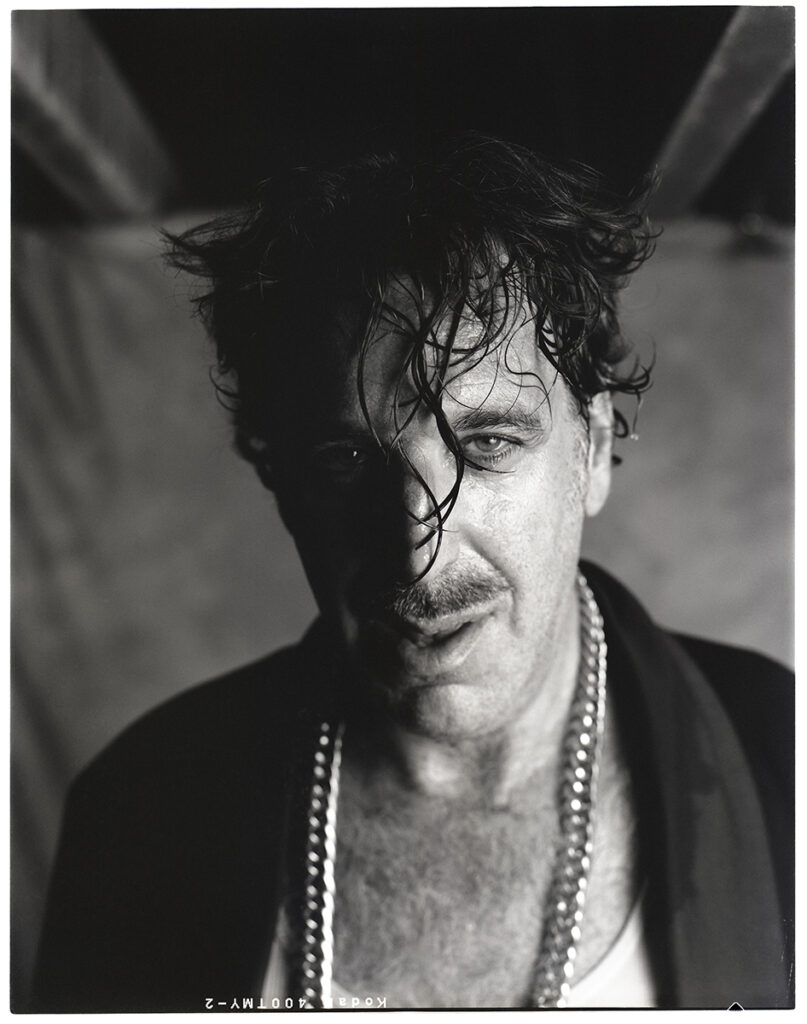

Chilly Gonzales

December 2024

Chilly Gonzales is a versatile artist known for his work across a range of genres, including classical, electro, rap, and jazz music. Throughout his career, he has balanced solo projects with notable collaborations. In 2024-2025, Chilly Gonzales is on tour for his new album Gonzo, offering a new chapter in his musical evolution.

Photographs by Victor Picon

Temple Magazine

Gonzo, your music has spanned a variety of genres, and you’ve continuously evolved as an artist, from your early days in Toronto to your time in Berlin, and later with the Solo Piano series. Now, with your new album Gonzo and the tour, you’re continuing to push musical boundaries. Looking back, how do you reflect on the years spent moving between Toronto and Berlin in the late 90s?

Chilly Gonzales

When I left Toronto, it was in some ways to escape certain mindsets. I felt that my ambition was too strong, but I hadn't yet learned certain lessons. I needed to be more and more myself, not trying to please everyone and presenting myself authentically. At that time, I was in a phase of positive discovery, realizing that the more I was myself, the better things worked, and very quickly. I'm talking about my early days in Berlin. Back then, I asked myself questions like: "Why can’t I be funny? Why can't I be arrogant?" In fact, these things didn't really have a place in music in Canada, because I was moving in an indie rock environment that took itself very seriously. There was no room for humor, and it was a false modesty. So, it was the opposite of what I felt, and all my instincts were pulling me in a different direction. When I arrived in Berlin, I started experimenting, incorporating arrogance, musical virtuosity, and humor—elements I now use to the fullest. And I saw that the reaction was much stronger and more positive than anything I had imagined in what I was doing in Canada. After this first shift, there was another moment where I reintegrated elements that had remained somewhat hidden, especially the musical virtuosity on the piano, which I highlighted in the first Solo Piano. Once those first five years were over, a new period began where I started finding a balance in what I was doing, mixing elements to make it resonate with people while staying authentically myself. Then, in 2009, I created my own label and added the name "Chilly Gonzales." It was a time when I truly found myself, when I found my audience, and when I could rely on them. That’s when I started playing about fifty concerts a year. So for me, it was really a journey: leaving Canada for five years, arriving at the first Solo Piano album, and then in 2009, beginning the modern, mature period I’m still in.

Temple Magazine

And throughout all these periods, you’ve explored many forms of art, various musical styles, you change format, tone, and register…

Chilly Gonzales

Not so much, at least in terms of musical style. There's rap, electro, of course, classical and jazz from my training. But there are also many styles I don't touch, like rock, indie, songwriting, reggae, drum and bass or rockabilly.

Temple Magazine

These four styles and the way you combine them, along with the evolution of your stage performances, evoke a vernacular approach, which resonates a lot with the Temple project, with the idea of not hierarchizing different art forms. Does that term resonate with you? Are there practices that you particularly prefer or rank yourself?

Chilly Gonzales

I rank them according to my taste, I would say. I'm very sensitive to shortcuts that others take, and I’ve taken some myself in my career. When you experiment, there are sometimes very positive surprises, but sometimes you learn the wrong lesson from that surprise. You think, "Ah, I found what works, I should just do that." There’s a temptation to take a shortcut. For me, when I first did Solo Piano, there was this temptation to follow up with Solo Piano 2, because that album expanded my audience so much. It allowed me to realize many other dreams, to play in concert halls, to have an audience that was less into musicology, less expert, less trendy in Paris, I don't know. But it widened my audience, and the level of affection they expressed for that album was deeper. So, there was a voice in my head saying, "Okay, you found the formula, let’s go, let’s just keep doing that!" But there was also another voice, thankfully, saying, "No, you found this because you were in a phase of experimentation, you didn’t even know it was going to work. You thought maybe your electro audience wouldn’t like your piano album. The lesson to learn is that you always have to follow where you want to go, in the passive sense of letting your unconscious guide you." Whether it's choosing: "Should I write lyrics? Should I collaborate with someone? Should I express myself on the piano?" I try to understand these questions by staying curious about what my unconscious tells me, rather than making overly strategic, calculated choices. Of course, you can't avoid calculation 100%, but at the beginning, I prefer to be passive and see where it leads me. That’s what allowed me to have a positive reaction with Solo Piano I. And so, I waited until 2012 to release Solo Piano 2. There were eight years between these two albums, even though I knew somewhere that it was what worked best and simplified my life in many ways. I could do big tours, play in concert halls by myself, which is quite easy to manage with a piano album. But I had to listen to my unconscious. That’s why I made the album Soft Power in 2008, a bit like a failed masterpiece. Then, I made Ivory Tower with Boys Noize, and my orchestrated rap album The Unspeakable Chilly Gonzales. So, I waited before making Solo Piano II, and the same goes for III. And if I ever make a fourth album, it will be the same. It’s because my unconscious is guiding me, and I am a slave to it. I’m the zombie who says: "Okay, piano, but it has to be authentic, I really need to have my say on the piano." Because if I had done what was easy and comfortable, we would still be talking about Solo Piano 18. And luckily, I wait for it to be sincere before doing it, and that’s what gives power to this album series.

Temple Magazine

You talk in your concerts about your collaborations with artists like Daft Punk and Philippe Katerine. How do you choose these collaborations? What makes you say: "I’m going to work with this artist"?

Chilly Gonzales

Most of the time, it’s the people who come to me. It’s more a question of my reactivity. Of course, there are times when I meet people, either in the music industry or by accident. If I’m a fan of someone and think I can learn something by spending time with them, I let them know I’m open to a collaboration, and then I wait a bit for the phone to ring, because that's how it should be done. You can’t sell yourself too much or insist. Sometimes, I have an idea for a project, like about a year ago, for a platform called Grünt. It’s an independent platform that invites rappers to create new tracks, freestyles, and features. A rapper can invite artists, or they can work alone with a few guests. I had the idea of doing a project around my piano work, with a bit of rap from me. But the main idea was to do new tracks with French-speaking rappers. The project was about creating bridges between different generations of rap in France, Germany, and even a bit in England. It’s a music I’ve loved for two decades, that’s deeply influenced me, but that I’ve explored mostly alone until now. For example, I was one of the few to rap on stage at the Philharmonie de Paris. Now, I want to build those bridges with people who have really invested in this music, and that’s what interests me most. For a project like this, of course, I do the research, but you also have to wait a bit for the enthusiasm to come from the other side. That’s what happened with Sheldon, a young rapper leading a crew called 75ᵉ Session. I started following Sheldon, and he contacted me to say he was a fan of what I did with piano and rap in the early 2010s. So, it was obvious I should invite him for this project, Grünt 63. They make a few of these each year.

On the other hand, with Philippe Katerine, I met him in the studio to play some keyboards on a new track. He enjoyed these moments, and that's where the idea of collaborating emerged. With Renaud Letang, we worked on Katerine - Robots After All. As for Daft Punk, they first asked me to do a remix in 2000. Then, 11 years later, they invited me to the studio. By coincidence, I had missed a flight to Los Angeles and ended up there without anything planned. I asked them if they were still in LA, and they said yes. So, I ended up in the studio listening to and playing some tracks. It wasn’t a planned project with a first-class plane ticket and a hotel booked. It happened organically and quite randomly.

That's what people need to understand: it's not a record label conspiracy forcing collaborations between big stars. It’s not that we always have the right idea. As musicians, we mostly want to create something spontaneous, where we find the right vibe without forcing it. There are a lot of happy accidents that happen before we get to the final product.

Temple Magazine

If you were to collaborate with someone outside of the music world, what kind of artist or creative person would you like to meet and work with?

Chilly Gonzales

Recently, I performed at the Paralympic Games in Paris with a talented choreographer, Alexander Ekman. He was the one who orchestrated the entire opening ceremony, and I really loved that experience. There was also a fashion designer, Louis Gabriel Nucci, who designed all the costumes. Even though we didn’t actually collaborate directly, I got to add my touch, and it was great to spend time with a high-level artist who doesn’t work in my field. I really enjoy moments like that, where I work with artists from other disciplines. I do this often, for example with music video directors or album cover designers. I also collaborated with Fabrice Caro, a comic book artist and novelist, who creates works that are both funny and deep, and that really touch me. He even designed the cover of my album French Kiss. I often find myself in this process, feeling a connection, a “return to myself” in the other person's work, and thinking we could maybe do something together. This kind of collaboration happens both in music and other fields, of course.

Temple Magazine

Temple Magazine

Gonzo, your music has spanned a variety of genres, and you’ve continuously evolved as an artist, from your early days in Toronto to your time in Berlin, and later with the Solo Piano series. Now, with your new album Gonzo and the tour, you’re continuing to push musical boundaries. Looking back, how do you reflect on the years spent moving between Toronto and Berlin in the late 90s?

Chilly Gonzales

When I left Toronto, it was in some ways to escape certain mindsets. I felt that my ambition was too strong, but I hadn't yet learned certain lessons. I needed to be more and more myself, not trying to please everyone and presenting myself authentically. At that time, I was in a phase of positive discovery, realizing that the more I was myself, the better things worked, and very quickly. I'm talking about my early days in Berlin. Back then, I asked myself questions like: "Why can’t I be funny? Why can't I be arrogant?" In fact, these things didn't really have a place in music in Canada, because I was moving in an indie rock environment that took itself very seriously. There was no room for humor, and it was a false modesty. So, it was the opposite of what I felt, and all my instincts were pulling me in a different direction. When I arrived in Berlin, I started experimenting, incorporating arrogance, musical virtuosity, and humor—elements I now use to the fullest. And I saw that the reaction was much stronger and more positive than anything I had imagined in what I was doing in Canada. After this first shift, there was another moment where I reintegrated elements that had remained somewhat hidden, especially the musical virtuosity on the piano, which I highlighted in the first Solo Piano. Once those first five years were over, a new period began where I started finding a balance in what I was doing, mixing elements to make it resonate with people while staying authentically myself. Then, in 2009, I created my own label and added the name "Chilly Gonzales." It was a time when I truly found myself, when I found my audience, and when I could rely on them. That’s when I started playing about fifty concerts a year. So for me, it was really a journey: leaving Canada for five years, arriving at the first Solo Piano album, and then in 2009, beginning the modern, mature period I’m still in.

Temple Magazine

And throughout all these periods, you’ve explored many forms of art, various musical styles, you change format, tone, and register…

Chilly Gonzales

Not so much, at least in terms of musical style. There's rap, electro, of course, classical and jazz from my training. But there are also many styles I don't touch, like rock, indie, songwriting, reggae, drum and bass or rockabilly.

![]()

Temple Magazine

These four styles and the way you combine them, along with the evolution of your stage performances, evoke a vernacular approach, which resonates a lot with the Temple project, with the idea of not hierarchizing different art forms. Does that term resonate with you? Are there practices that you particularly prefer or rank yourself?

Chilly Gonzales

I rank them according to my taste, I would say. I'm very sensitive to shortcuts that others take, and I’ve taken some myself in my career. When you experiment, there are sometimes very positive surprises, but sometimes you learn the wrong lesson from that surprise. You think, "Ah, I found what works, I should just do that." There’s a temptation to take a shortcut. For me, when I first did Solo Piano, there was this temptation to follow up with Solo Piano 2, because that album expanded my audience so much. It allowed me to realize many other dreams, to play in concert halls, to have an audience that was less into musicology, less expert, less trendy in Paris, I don't know. But it widened my audience, and the level of affection they expressed for that album was deeper. So, there was a voice in my head saying, "Okay, you found the formula, let’s go, let’s just keep doing that!" But there was also another voice, thankfully, saying, "No, you found this because you were in a phase of experimentation, you didn’t even know it was going to work. You thought maybe your electro audience wouldn’t like your piano album. The lesson to learn is that you always have to follow where you want to go, in the passive sense of letting your unconscious guide you." Whether it's choosing: "Should I write lyrics? Should I collaborate with someone? Should I express myself on the piano?" I try to understand these questions by staying curious about what my unconscious tells me, rather than making overly strategic, calculated choices. Of course, you can't avoid calculation 100%, but at the beginning, I prefer to be passive and see where it leads me. That’s what allowed me to have a positive reaction with Solo Piano I. And so, I waited until 2012 to release Solo Piano 2. There were eight years between these two albums, even though I knew somewhere that it was what worked best and simplified my life in many ways. I could do big tours, play in concert halls by myself, which is quite easy to manage with a piano album. But I had to listen to my unconscious. That’s why I made the album Soft Power in 2008, a bit like a failed masterpiece. Then, I made Ivory Tower with Boys Noize, and my orchestrated rap album The Unspeakable Chilly Gonzales. So, I waited before making Solo Piano II, and the same goes for III. And if I ever make a fourth album, it will be the same. It’s because my unconscious is guiding me, and I am a slave to it. I’m the zombie who says: "Okay, piano, but it has to be authentic, I really need to have my say on the piano." Because if I had done what was easy and comfortable, we would still be talking about Solo Piano 18. And luckily, I wait for it to be sincere before doing it, and that’s what gives power to this album series.

Temple Magazine

You talk in your concerts about your collaborations with artists like Daft Punk and Philippe Katerine. How do you choose these collaborations? What makes you say: "I’m going to work with this artist » ?

Chilly Gonzales

Most of the time, it’s the people who come to me. It’s more a question of my reactivity. Of course, there are times when I meet people, either in the music industry or by accident. If I’m a fan of someone and think I can learn something by spending time with them, I let them know I’m open to a collaboration, and then I wait a bit for the phone to ring, because that's how it should be done. You can’t sell yourself too much or insist. Sometimes, I have an idea for a project, like about a year ago, for a platform called Grünt. It’s an independent platform that invites rappers to create new tracks, freestyles, and features. A rapper can invite artists, or they can work alone with a few guests. I had the idea of doing a project around my piano work, with a bit of rap from me. But the main idea was to do new tracks with French-speaking rappers. The project was about creating bridges between different generations of rap in France, Germany, and even a bit in England. It’s a music I’ve loved for two decades, that’s deeply influenced me, but that I’ve explored mostly alone until now. For example, I was one of the few to rap on stage at the Philharmonie de Paris. Now, I want to build those bridges with people who have really invested in this music, and that’s what interests me most. For a project like this, of course, I do the research, but you also have to wait a bit for the enthusiasm to come from the other side. That’s what happened with Sheldon, a young rapper leading a crew called 75ᵉ Session. I started following Sheldon, and he contacted me to say he was a fan of what I did with piano and rap in the early 2010s. So, it was obvious I should invite him for this project, Grünt 63. They make a few of these each year.

On the other hand, with Philippe Katerine, I met him in the studio to play some keyboards on a new track. He enjoyed these moments, and that's where the idea of collaborating emerged. With Renaud Letang, we worked on Katerine - Robots After All. As for Daft Punk, they first asked me to do a remix in 2000. Then, 11 years later, they invited me to the studio. By coincidence, I had missed a flight to Los Angeles and ended up there without anything planned. I asked them if they were still in LA, and they said yes. So, I ended up in the studio listening to and playing some tracks. It wasn’t a planned project with a first-class plane ticket and a hotel booked. It happened organically and quite randomly.

That's what people need to understand: it's not a record label conspiracy forcing collaborations between big stars. It’s not that we always have the right idea. As musicians, we mostly want to create something spontaneous, where we find the right vibe without forcing it. There are a lot of happy accidents that happen before we get to the final product.

Temple Magazine

If you were to collaborate with someone outside of the music world, what kind of artist or creative person would you like to meet and work with?

Chilly Gonzales

Recently, I performed at the Paralympic Games in Paris with a talented choreographer, Alexander Ekman. He was the one who orchestrated the entire opening ceremony, and I really loved that experience. There was also a fashion designer, Louis Gabriel Nucci, who designed all the costumes. Even though we didn’t actually collaborate directly, I got to add my touch, and it was great to spend time with a high-level artist who doesn’t work in my field. I really enjoy moments like that, where I work with artists from other disciplines. I do this often, for example with music video directors or album cover designers. I also collaborated with Fabrice Caro, a comic book artist and novelist, who creates works that are both funny and deep, and that really touch me. He even designed the cover of my album French Kiss. I often find myself in this process, feeling a connection, a “return to myself” in the other person's work, and thinking we could maybe do something together. This kind of collaboration happens both in music and other fields, of course.

![]()